Johnson’s Island Masonic Memorial Day Service

|

General Masonic attendance at the event has grown over the years and the event is regularly attended by Grand Lodge Officers, District Deputies, and many brethren from Ohio and other states. Other Masonic groups represented, Order of the Eastern Star Port Clinton Chapter No. 267

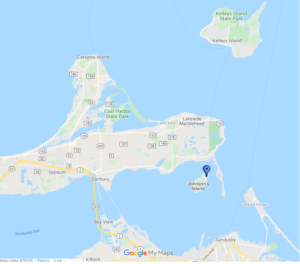

Click Here to go to Google Maps |

The Confederate Prison on Johnson’s Island

presented by Rodney R. Zerkle to the Ohio Chapter of Research, R.A.M. June 18, 1994

Johnson’s Island is located just inside the mouth of Sandusky Bay, 1 mile from the Marblehead Peninsula and approximately 2¾ miles from the City of Sandusky. Today, Johnson’s Island is the summer home for several hundred summer residents. From April 1862 to September 1865, Johnson’s Island was the site of a unique Confederate prison.

Johnson’s Island is located just inside the mouth of Sandusky Bay, 1 mile from the Marblehead Peninsula and approximately 2¾ miles from the City of Sandusky. Today, Johnson’s Island is the summer home for several hundred summer residents. From April 1862 to September 1865, Johnson’s Island was the site of a unique Confederate prison.

When it became apparent that there would be no quick resolution to the Civil War, Lieutenant Colonel William Hoffman was appointed Commissary-General of Prisoners for the Northern states and given the task of developing a prison system. In particular Hoffman was directed to locate “a depot for prisoners of war” among the islands of Lake Erie.

In the middle of October 1861, Hoffman traveled to Sandusky and toured the various Lake Erie Islands, seeking a suitable prison location. He ruled out North Bass and Middle Bass Islands because of their close proximity to Canada and the problems of providing adequate supplies during the winter. South Bass Island, on which the Village of Put-in-Bay is located, was rejected because it would be too expensive to lease suitable lands and because residents feared damage to their extensive vineyards. The residents of Kelly’s Island were more amenable to providing a suitable prison site, but Hoffman was again concerned about damage to vineyards, and he was also concerned about the temptation to the soldiers presented by the wine and brandy industries of the island.

Finally Hoffman turned his attention to Johnson’s Island. Johnson’s Island is about 300 acres in size and was owned in its entirety by Leonard B. Johnson. Forty acres of the island had been cleared of trees and would make an excellent prison site. The remaining trees could be used as fuel. Half of the island was leased for $500.00 and the Federal government was given exclusive control of the entire island.

Arrangements were quickly finalized with the Sandusky construction firm of Gregg and West to build a prison for under $30,000.00. A fairly consistent freeze during the winter of 1861-1862 facilitated the transfer of material over the ice from Sandusky to Johnson’s Island. The prison was ready for occupancy in late February 1862, but because of a variety of delays it was not opened until April of 1862.

The prison consisted of a 15-acre enclosure surrounded by a plank stockade 14 feet in height. There were 13 barracks or “blocks” for the prisoners, perhaps to correspond to the 13 stars in the Confederate flag. Each block was two stories high, and one of the blocks was designated as a prison hospital. Buildings were constructed to house the garrison guarding the prisoners and other structures were added as needed. Ultimately, the prison complex consisted of approximately 100 buildings that included such diverse structures as a sutler’s store, a bakery, a limekiln, an icehouse, stables, forts, a powder magazine, and a barbershop.

When first developed, Johnson’s Island was to have housed Confederate prisoners of all ranks, but from June 1862 onward, it was especially intended for Confederate officers—the only prison so designated. This switch resulted in the transfer to Johnson’s Island of hundreds of Confederate officers from Camp Chase in Columbus. The designation of Johnson’s Island as an officers prison may been the result of administrative problems at Camp Chase. There had been persistent complaints that Confederate officers were receiving very lax treatment in Columbus, including being able to come and go from Camp Chase at will, being able to wander the streets of Columbus in full Confederate uniform, and being able to register at the best hotels as belong to “C. S. Army.”

An estimated total of 12,000 to 15,000 Confederates were confined to Johnson’s Island during the forty months that the prison was in operation. The population varied greatly from month to month, depending primarily on how well the prisoner exchange program between the North and the South was functioning. The prison population increased during the early months of operation but decreased to a low of seventy-three in May 1863. When the exchange agreements began to collapse, the prison population again began to rise with a monthly average of 2,549 from July 1863 to June 1865.

Ohio Governor William Dennison was requested to supply the guards for the camp. Four companies of men were recruited and formed into a unit designated as the Hoffman Battalion. The recruits were given a $100.00 signing bonus and a promise of good pay, excellent quarters, and abundant rations. Rumors that the enrollees would not have to serve in any location other than Johnson’s Island aided the recruitment process.

William Pierson, a local businessman and mayor of Sandusky, was placed in charge of the Hoffman Battalion and the operation of the prison. Pierson was a Yale graduate and a member of Science Lodge No. 50, located in Sandusky and chartered in 1820. Although he was a successful businessman and politician, he had no previous military experience and was apparently not an able prison administrator. He promulgated a series of arbitrary rules that tended to insult the prisoners and ferment discontent, and he allowed a general lack of discipline to develop among the guards. Sanitary conditions steadily deteriorated within the prison because of the accumulation of garbage and because of problems associated with the development of latrines (only a few inches of soil covered the limestone base of the island). Pierson was later replaced by a camp commander with more military training and better administrative skills.

Despite the problems mentioned above, except for the winter, prison life on Johnson’s Island was not altogether unpleasant. The food rations were adequate in quantity, at least during the early part of the war. Clothing and blankets were issued to destitute prisoners. Moreover, the prisoners were permitted to receive packages from relatives and friends that included food, clothing, and money. Additional food and clothing and a variety of other supplies could be purchased from the prison’s sutler. In fact, for most of the war, almost any item that was available in Sandusky was also available on Johnson’s Island, but at a rather inflated price.

One needs to remember that the officers confined to Johnson’s Island were well educated and a large part of the Southern elite. The prisoners were permitted to subscribe to newspapers such as the New York Herald and the Cincinnati Enquirer, although the Enquirer was later banned because of its secessionist sympathies. (The Sandusky Register was intensely disliked because of its strong anti-slavery stance.) The prisoners wrote and produced minstrel shows, organized a baseball league, wrote poetry, held classes on a variety of subjects, and operated a library that included 600 books from the YMCA. There was a chaplain assigned to the prison and regular Sunday services were conducted.

Winter provided the most difficult of conditions. Many of the prisoners were from the Deep South without prior experience with Northern winters, and many did not have sufficient clothing and blankets. The hastily constructed prison structures had no foundations, no ceilings (although by the winter of 1864-65 most had been ceiled), and only a single layer of warped knotty lumber to keep out the bitter wind that sweeps across Sandusky Bay. Sub-zero temperatures are not uncommon during Lake Erie winters and the combination of strong winds and frigid temperatures produced much misery among the prisoners.

In the latter two years of the war, as the conditions of Andersonville and other Southern prisons become known, conditions at Johnson’s Island became more stringent. The food rations were sharply decreased, the issuance of clothing and blankets restricted, the sutler’s store was closed, and the mailings of food and clothing were intercepted. Simultaneously, the prison population was increasing, at one point reaching 3,256, and tents had to be used to house the excess population. Partly out of necessity and partly out of boredom, rat hunts were organized. The rats were roasted, fried, boiled into a stew, or baked into a pie. In one successful hunt, over 500 rats were killed.

Given the harshness of the winters, the poor sanitation, and the variety of other hardships that the prisoners endured, the records of Johnson’s Island indicate a surprisingly few number of deaths. Only 221 deaths are recorded for the total of 12,000 – 15,000 prisoners. This 2% mortality rate compares very favorably to other prisons of the period. In November 1863 Johnson’s Island had 16 deaths out of a population of 2,381, while Camp Morton, another Federal Prison located at Indianapolis, had 40 deaths out of a population of 2,831. More than twelve thousand Federal prisoners died during the single year that the prison in Andersonville was in operation. During August alone of 1864, the death toll at Andersonville was 2,993.

Masonic Prisoners

It has been estimated that approximately half of the prisoners that passed through Johnson’s Island were Masons. Regular lodge meetings were held, sometimes attended by Yankee guards. A special ward within the hospital was reserved for Masons, and ailing Masons were never left to suffer and die alone. On one occasion, a non-Mason pretended to be a member in hope of receiving better treatment. He was easily discovered and moved. In December 1864, when the food supply had been decreased, the President of the Masonic Prison Association appealed to the camp commander on behalf of the sick (both Mason and non-Masons) and requested that they be allowed to purchase fruit and other needed items from the prison sutler.

It has been estimated that approximately half of the prisoners that passed through Johnson’s Island were Masons. Regular lodge meetings were held, sometimes attended by Yankee guards. A special ward within the hospital was reserved for Masons, and ailing Masons were never left to suffer and die alone. On one occasion, a non-Mason pretended to be a member in hope of receiving better treatment. He was easily discovered and moved. In December 1864, when the food supply had been decreased, the President of the Masonic Prison Association appealed to the camp commander on behalf of the sick (both Mason and non-Masons) and requested that they be allowed to purchase fruit and other needed items from the prison sutler.

Masons who died on Johnson’s Island and who were returned to their families were shipped home in metallic coffins provided by Masonic contributions. Members of the fraternity provided for both Masons and non-Masons the cedar boards used to mark the graves in the prison cemetery.

There were persistent rumors that prisoners were allowed to travel to Sandusky to attend meetings of Science Lodge No. 50 and Perseverance Lodge No. 329, which was chartered in 1860 and is also located in Sandusky. As the time of this writing, “Masonic furloughs” to Sandusky cannot be confirmed from prisoners’ diaries, and unfortunately, most of the records of Science and Perseverance Lodges were destroyed in a 1943 fire. In any event, records indicate that the lodges did collect money and goods for use by the prisoners.

After the conclusion of the war, Johnson’s Island reverted back to the control of L. B. Johnson. Auctions were held in late 1865 and the spring of 1866 to dispose of much of the stores and buildings. The small arms and munitions were transferred to the Detroit Arsenal and the larger guns were sent to Fort Wayne, near Detroit. Activities such as agriculture, quarrying, and the development of short-lived summer resorts in 1884 and 1904 have obliterated almost all evidences of the prison.

Little was done with the cemetery until 1890 when the rotting cedar headboards of the 206 graves were replaced with stones of white Georgian marble. In 1910 a bronze statue of a Confederate soldier was erected under the initiative of the Robert Patton Chapter of the United Daughters of the Confederacy, of Cincinnati. The statue was cast in Rome by Moses Ezekiel and is placed on a stone base provided by the Grand Lodge of Mississippi “in remembrance of the Masons who sleep here.” On two sides of the base is the inscription “CONFEDERATE SOLDIERS. THEY WERE MASONS.”

Of the 206 Confederate soldiers buried on Johnson’s Island, Masonic affiliation has been confirmed for 27. Only one of the tombstones, that of Carter W. Gillespie, a captain of the 65th (or 66th) North Carolina Cavalry, bears a Masonic emblem. The non-government issue marker is easily identified because it is pointed on the top (most of the markers are rounded), and it is the tallest marker in the cemetery. It was placed prior to the placing of the other markers in 1890 and apparently by Gillespie’s family. Little is known, however, about Gillespie himself or why he alone of all his brethren should have been selected for this special mark of distinction.

Currently, the care and upkeep of the cemetery is under the jurisdiction of the Dayton Memorial Cemetery which, in turn, is under the jurisdiction of the Department of Veteran Affairs. There is a local caretaker that does routine maintenance and grounds keeping, and visitors to the cemetery are usually favorable impressed by its excellent appearance.

For approximately the past 30 years, the Johnson’s Island Association under the leadership of Ronald E. Doll, a member of Parkside Lodge No. 736, has sponsored a Memorial observance on the Sunday preceding Memorial Day. Participants include members of the clergy, veterans organizations, and various local dignitaries. Oliver H. Perry Lodge No. 341 of Port Clinton, under dispensation from the Grand Lodge of Ohio, conducts a brief service that involved the placing of a white apron and sprigs of evergreen in front of the statue of the Confederate soldier.

The 206 Confederates who now lie in eternal slumber on Johnson’s Island may have experienced much pain, suffering, and loneliness as they passed from this transitory world, but hopefully their eternal spirits are comforted by the fact that their memories live on.

Bibliography

Downer, Edward T. “Johnson’s Island”. An otherwise unidentified monograph in the Johnson’s Island file of the Ida Rupp Public Library, Port Clinton.

Frohman, Charles E. Rebels on Lake Erie. Columbus, Ohio: Southard Company, 1965

Hesseline, William B. Civil War Prisons New York: Frederick Ungar Publishing, 1964

Long, Roger. “Johnson’s Island Prison.” Blue and Gray Magazine, IV, No. 5 (February-March 1987), 6-31 and 45-63.

Long, Roger. “They Were Masons: The Rebels on Johnson’s Island.” The Scottish Rite Journal. XCIX, No. 9 (September 1991), 31-36